Discover more from The Trading Resource Hub

Lessons From a Chess and Tai Chi Champion on the Art of Learning and Optimal Performance

Adding nuance to my previous post, with help from an autobiography that discusses psychology

Yes, you read that subtitle right. You’re about to receive notes from me on a psychology book. Specifically, Josh Waitzkin’s The Art of Learning: An Inner Journey to Optimal Performance.

Adding nuance to my previous post

I wasn’t expecting to be writing this stack either, given my publicly self-declared scepticism about trading psychology books1 (not the concept of trading or performance psychology). But I felt I had a point to prove: that I do understand that to truly excel in any field where performance is critical, you have to master your mind as well as the necessary technique.

This doesn’t, in my view, compete with the opinion that you should start with identifying your technical edge, though, if you haven’t truly mastered the mechanical side of things yet. If you have even the slightest bit of doubt about whether your strategy really works — and this will affect your psychology — then I honestly do believe that some hard studying will do wonders for this.

Having said that, this very likely isn’t in itself enough to ensure exceptional returns. To become a champion trader. It certainly can be sufficient to push struggling traders into profitability, however, or at least see their performance significantly improve. In itself, that will help build confidence, which obviously links to psychology. This was the main message I wanted my previous post to deliver — but I realise I could’ve made that clearer. Lesson learned.

So, let’s be clear now. That post was not aimed at everyone. It was aimed at the people who look towards psychology books as a ‘fix’ for their trading problems, when they simply haven’t put in enough (or the right type of) work into developing the ideal system for them. Who perhaps even have a tendency to ‘blame’ their psychology to avoid taking responsibility for their own trading.

That is not every trader, nor every reader of this Substack. But there does seem to be a substantial number of traders who do these things, who I think are well-served by spending more time studying market mechanics and their own journals first, as well as understanding that this helps their psychology. It improves it. I didn’t say that it fixes it. But we can all only improve one step at a time, and most traders are at the stage in their journey where studying mechanics will simultaneously help their mindset. Two for the price of one! Moreover, what I suggested were relatively simple things that anyone can do, so long as they put their mind to it.

I never intended to give the impression that there’s no such thing as trading or performance psychology, and I apologise if I did. So today, I’m taking a look at what we can learn about performance psychology from a master in multiple disciplines (I think it’s fair to assume that someone like that knows a thing or two about how to optimise performance), and how we can apply those principles to trading.

Keep the feedback coming!

I realised my lack of clarity — at least on these points — relatively quickly thanks to your feedback. I’m really grateful for it — without it, it’s difficult to know how I can improve. Please continue to share your feedback, in whatever format you’re comfortable with! Leave a comment below, message me on Twitter or email me at kayklingson@yahoo.com.

Why this book

As I said, this isn’t a trading psychology book, but more a book about learning and optimising performance in general. However, since the author is a master — a champion, in fact — in two fields not obviously related (chess and tai chi), I think he’s certainly someone worth listening to and learning from, whether you seek to optimise your trading performance only, or your performance in other endeavours too.

But I will also say right off the bat that the lessons to be gained from this book will differ per reader — for instance, it can be to simply get an insight into the level of dedication required, their typical way of thinking and the way they resolve obstacles. In other words: to be inspired — perhaps to work harder, perhaps to stop seeing setbacks as failures, or perhaps something else altogether. Or it can be to deploy the concrete techniques suggested by the author.

From where I’m standing, any of these are valid ways of getting something out of the book. However, you can learn such lessons in other ways too, particularly if books aren’t your thing — by intently reviewing the Qullamaggie streams, for example. Kristjan never ceases to inspire me with the amount of work he has — and obviously still does — put into his craft and passion. Furthermore, he’s shown us what is possible with some very hard work — I don’t know about anyone else, but it certainly pushes me to work harder whenever I’m slacking off (or heading that way).

Going back to the book I’m discussing today, another reason I chose it to help me make my points was that I was hoping that a good number of you aren’t familiar with this book or author, giving me a reasonable chance at sharing something new and hopefully interesting with you. And even for the readers who have heard of the book, I hope to add value by discussing how its lessons can be linked to trading, which relatively few people have done to date, and none do it in anything like my writing style.

About my notes

As ever, my notes are no substitute for consuming the full resource — in this case, reading the book. They simply pick out what I felt were the highlights for me and link/apply them to trading, with my own insights where I think they add value.

If my notes give you the impression that the book may hold value for you — please do look it up. If not, then don’t! This stack is not intended as a book review, but for educational purposes only. I hope to give you food for thought, and that you share some of those thoughts in the comments below, so you can provoke some in me in return. I’m here to learn too.

Small confession: I read this book nearly a year ago now, in context of pushing myself to the next level in another endeavour (not chess or tai chi, by the way), in which I was ready to take that next step, because I had advanced technique by that point. I took notes for my then-teacher, which I used as the basis for this article.

Without further ado, my notes on The Art of Learning: An Inner Journey to Optimal Performance by Josh Waitzkin — part autobiography, and part practical psychology.

(Any time I write about psychology — or, for that matter, anything else — it’s always going to be practical! I remain a technical writer at heart.)

Incremental learning

In virtually any ambitious field — sports, acting, music, etc. — we see comparable dynamics:

“Inevitably dreams are dashed, hearts are broken, most fall short of their expectations because there is little room at the top. […]

“Two questions arise. First, what is the difference that allows some to fit into that narrow window to the top? And second, what is the point? If ambition spells probable disappointment, why pursue excellence?

“In my opinion, the answer to both questions lies in a well-thought-out approach that inspires resilience, the ability to make connections between diverse pursuits, and day-to-day enjoyment of the process. The vast majority of motivated people, young and old, make terrible mistakes in their approach to learning. They fall frustrated by the wayside while those on the road to success keep steady on their paths.”

Two theories of intelligence

Josh points to a leading developmental psychologist, Dr. Carol Dweck, who makes the following distinction between implicit theories of intelligence:

The entity theory, where the person attributes their success or failure to an ingrained — and unalterable — level of intelligence, ability or skill.

The incremental theory, where the person attributes their success or failure to hard work (or lack thereof).

I think you can guess which one I subscribe to after my previous post. And here’s what Josh says:

“with hard work, difficult material can be grasped—step by step, incrementally, the novice can become the master.”

Josh also pointed to an interesting study, where a group of kids were given several sets of maths problems to solve. The first set was easy, so everyone solved them correctly. The second set was too difficult for everyone — all the kids got it wrong, but the entity theorists among them felt dismay at the challenge, while the incremental theorists saw the challenge as exciting. The third set was, once again, easy. But only the incremental theorists breezed through them. The entity theorists’ self-confidence was so destroyed by the preceding set, which they had not been able to solve, that they foundered through the easy stuff.

Is it mindset or intelligence?

Josh explains an interesting inverse correlation with intelligence:

“the results have nothing to do with intelligence level. Very smart kids with entity theories tend to be far more brittle when challenged than kids with learning theories who would be considered not quite as sharp. In fact, some of the brightest kids prove to be the most vulnerable to becoming helpless, because they feel the need to live up to and maintain a perfectionist image that is easily and inevitably shattered. […] some of the most gifted [chess] players are the worst under pressure, and have the hardest time rebounding from defeat.”

I have heard similar stories regarding traders, from a range of people. It’s also akin to being unable to cut losses quickly for ego reasons — because of a feeling of disbelief that you could possibly be wrong. Josh made a similar analogy in a tai chi context:

“While I learned with open pores—no ego in the way—it seemed that many other students were frozen in place, repeating their errors over and over, unable to improve because of a fear of releasing old habits. When Chen [their tai chi master] made suggestions, they would explain their thinking in an attempt to justify themselves. They were locked up by the need to be correct.”

The key lessons

Anyway, as for the takeaway of the two theories of intelligence, I think that the main lessons are to:

Stop thinking in terms of talent — whether in trading or something else; and

Start thinking in terms of what small, achievable steps you need to take next to get closer to where you want to be.

Invest in loss: make peace with imperfection

The principle of incremental learning — that anyone can learn with hard work, broken up into incremental steps — is heavily linked to the principle of being able to invest in loss.

When you learn incrementally, there will be some steps back among all the steps forward. There will be losses on the way, be it a lost match or a losing trade.

A benefit of trading

I personally think that we’re lucky to be aiming at high performance in trading, as opposed to virtually any other competitive activity. We’re constantly losing — which gives us plenty of opportunities to learn and grow — but more importantly, we can have more losing than profitable trades, yet overall comfortably come out as a winner. For example, Kristjan’s account growth is well-documented, yet he typically has around a 25% strike rate.

The frequency at which we practically must lose enables us to become naturally resilient. To not be “brittle”, to borrow Josh’s choice of word earlier. To not be fragile in our confidence, and therefore not risk falling apart whenever we suffer a loss. (Suffering a big loss may be a different story, but that’s what risk management is for.)

Developing resilience

When someone is resilient, they are able to invest in their loss. They can take that loss, ask themselves what they can learn from it, then come back stronger. In a trading context, that loss was merely a tuition fee you paid the market. In short: by believing that you’re not perfect — by believing (and ideally knowing) you regularly make mistakes, you can always be on the lookout for flaws to improve.

But what you shouldn’t do is see your losses as failures. I think this is a good moment for a Mark Minervini tweet:

“Persistence is more important than knowledge because skill can be developed, but nothing great comes to those who quit. Make an unconditional commitment to learning from the best and learning from your mistakes and you will not fail. Believe in yourself and never give up.”

What about a big win?

This is what Josh wrote on how to see big wins:

“When we have worked hard and succeed at something, we should be allowed to smell the roses. The key, in my opinion, is to recognize that the beauty of those roses lies in their transience. It is drifting away even as we inhale. We enjoy the win fully while taking a deep breath, then we exhale, note the lesson learned, and move on to the next adventure.”

Continual self-improvement

Investing in your losers — seeing every loss as a learning opportunity — is a key input to any continual improvement process you adopt for yourself.

For example, I’m always asking for feedback, because I’m always seeking to get better, and external feedback provides critical input to know what I should be improving — as a writer, anyway.

A Lance Beggs (YTC) suggestion

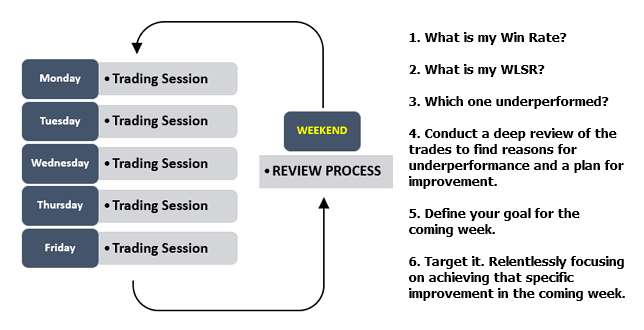

As a trader, you could take an approach as suggested by Lance Beggs (from YourTradingCoach.com, who is unfortunately taking a permanent hiatus on that website — a real loss to the trading community):

In essence, these are the steps you can take to make small, incremental improvements on a continual basis:

Review your trades. Take a hard look at your numbers.

Identify your weakest area — the one thing you most need to improve to improve your bottom line. (Note: it does not need to push you into profitability yet — it just has to improve your bottom line, i.e. have you lose less money, if you’re still consistently losing.)

Make a plan for how for the next trading period (e.g. over the course of the next week), you’re going to improve that one area. For example: cutting losers quicker, not taking any unplanned trades or improving your average winner in % terms.

At the end of that period, review how you did. Did you achieve what you set out to do? Congratulations, you’ve improved! Now do the same thing again for this period’s results: identify the one area that was the weakest, and improve it over the course of the next trading period. And so on.

As an aside, this reasonably aligns to something I regularly write about at work, which some of you may be familiar with too: the plan–do–check–adjust (PDCA) cycle.

Personal reflection

I suppose it’s both my good and bad fortune that this trait — constantly seeking to improve — is simply a part of me. I needed no book to tell me that seeking continual improvement is key to becoming truly great at something, regardless of whether this is in context of improving technique, mindset or both.

Maintain balance

That trait can be bad, in that I sometimes push myself too hard (and I doubt I’m alone in this). As such, bear in mind the following advice from Josh:

“There is the careful balance of pushing yourself relentlessly, but not so hard that you melt down. Muscles and minds need to stretch to grow, but if stretched too thin, they will snap.

“A competitor needs to be process-oriented, always looking for stronger opponents to spur growth, but it is also important to keep on winning enough to maintain confidence. We have to release our current ideas to soak in new material, but not so much that we lose touch with our unique natural talents. Vibrant, creative idealism needs to be tempered by a practical, technical awareness.”

‘Making smaller circles’

This phrase from Josh boils down to incrementally fine-tuning very small, simple movements to refine fundamental principles. His goal was to sharpen his “feeling” for tai chi:

“When through painstaking refinement of a small movement I had the improved feeling, I could translate it onto other parts of the form, and suddenly everything would start flowing at a higher level. The key was to recognize that the principles making one simple technique tick were the same fundamentals that fueled the whole expansive system of Tai Chi Chuan.

“This method is similar to my early study of chess, where I explored endgame positions of reduced complexity […] in order to touch high-level principles such as the power of empty space, zugzwang (where any move of the opponent will destroy his position), tempo, or structural planning. Once I experienced these principles, I could apply them to complex positions because they were in my mental framework. […]

“It would be absurd to try to teach a new figure skater the principle of relaxation on the ice by launching straight into triple axels. She should begin with the fundamentals of gliding along the ice, turning, and skating backwards with deepening relaxation. Then, step by step, more and more complicated maneuvers can be absorbed, while she maintains the sense of ease that was initially experienced within the simplest skill set.”

Incidentally, this is why I felt my last stack — where the mechanical side of trading links to psychology — was the right place to start in terms of trading psychology. If you haven’t even developed a system yet that at least on paper makes money, I don’t think you’re ready to start considering how to improve your execution.

Fear the man who has practiced one kick 1,000 times, not the man who practiced 1,000 kicks once

I found it interesting to learn how — much like in trading — you don’t need a big repertoire in tai chi to be able to win, even at national competition level:

“So, in my Tai Chi work I savored the nuance of small morsels. The lone form I studied was William Chen’s, and I took it on piece by piece, gradually soaking its principles into my skin. […]

“It soon became clear that the next step of my growth would involve making my existing repertoire more potent. It was time to take my new feeling and put it to action. […]

“My understanding of this process […] is to touch the essence (for example, high refined and deeply internalized body mechanics or feeling) of a technique, and then to incrementally condense the external manifestation of the technique while keeping true to its essence.

“Over time expansiveness decreases while potency increases. I call this method ‘Making Smaller Circles.’”

The chapter goes on for much longer, which you can always read for yourself if you’re interested, but I think the analogy to trading is pretty clear. Learn one setup. Master it by studying it in different market conditions and taking note of all the nuances. Strike rates are only partially inherent to your chosen setup or strategy — the other part relates to your ability to read the environment and your eye for detail.

Avoid internal conflict

“I was a talented kid [at chess] with good instincts who had been beating up on street hustlers who lacked classical training. Now it was time to slow me down and properly arm my intuition, but Bruce [Josh’s first chess teacher] had a fine line to tread. He had to teach me to be more disciplined without dampening my love for chess or suppressing my natural voice. Many teachers have no feel for this balance and try to force their students into cookie-cutter molds.”

Essentially, the lesson here is that you must stay true to who you are. Quite the cliché, but one that holds true. Your performance can never be optimal if you must quell your instincts, your natural voice, to do as someone else tells you to. It doesn’t matter whether that someone is the author of your favourite book, a stream host, a big Twitter trader or your personal coach. Instead, take their ideas — especially the principles behind them — and adapt them to fit your own personality.

The Qullamaggie approach

Qullamaggie wrote the following on his website, which I think takes pretty much the same point of view:

“I learned from a lot of people; I was in many different chat rooms and trading communities, went to seminars, read a lot of books, articles etc. Picked up bits and pieces and developed my own thing that fits my own personality.”

How to integrate new knowledge

In essence, you should take in new information and integrate it with what you already know, while ensuring that it doesn’t violate who you are inside. Don’t be hindered by internal conflicts — something Josh sees as “fundamental to the learning process”:

“We have to release our current ideas to soak in new material, but not so much that we lose touch with our unique natural talents.”

Later in the book, he added:

“I believe that one of the most critical factors in the transition to becoming a conscious high performer is the degree to which your relationship to your pursuit stays in harmony with your unique disposition. There will inevitably be times when we need to try new ideas, release our current knowledge to take in new information—but it is critical to integrate this new information in a manner that does not violate who we are. By taking away our natural voice, we leave ourselves without a center of gravity to balance us as we navigate the countless obstacles along our way.”

A trading example

Holding periods are, I think, a good example in a trading context. Many traders who trade the same setup (should) buy at more or less the same point, but use different exit strategies.

The traders who hold a stock for weeks or even months want to prioritise things like minimising screen time and catching the bulk of the longer-term move, and don’t mind sitting through pullbacks and ultimately giving back a chunk of their profits, nor do they mind low strike rates. They often exit when the price action is showing signs of weakness, like the stock losing a key support level.

Shorter-term traders don’t mind more screen time and being more active (and in fact may actually like this), but prefer to move their money around faster and compound it quicker that way. Many also have a poor tolerance for low strike rates and giving a significant chunk of their paper profits back. As such, they tend to sell into strength, then roll their money into the next breakout (or whatever your setup is).

Objectively speaking, neither group is ‘wrong’. At the end of the day, the goal is to make money. So long as you do so legally, it doesn’t matter how.

But for many traders, one of these approaches may be wrong for them. You should trade in a way that suits your personality (and lifestyle and commitments). Do what comes easiest to you. More importantly, do what makes you the most money, but that often boils down to the same thing, especially in the long run.

Every strategy will go through periods where it doesn’t work well. If you also have some sort of fundamental problem with the strategy you’ve chosen (like giving back too much profit, or missing out on big chunks of the overall move), you’ll effectively be battling yourself, and will struggle to maintain discipline. Even if you can maintain it, the energy it takes to suppress your instincts will have a price — if nothing else, suboptimal performance.

Profitable instincts

How do you develop the right instincts — by which I mean instincts that are profitable for you? (I wanted to address this question because many traders start out doing the exact opposite of what they should do, like cutting winners quickly and letting losers run.)

You study. You must study hard and smart enough to truly believe that your strategy is right for you. And when you see it making money, you’ll strengthen those beliefs. It’ll give you confidence and conviction, which will improve your execution.

Think about the process, not just the outcome

Josh’s teacher Bruce presented himself as more of a guide than an authority. Bruce asked Josh questions, and to explain his thought processes on important decisions, regardless of whether Josh had made a good or a bad decision. This slowed Josh down where necessary, but clearly also plays a huge role in the learning process.

Linking this to trading

To think about this in trading terms, a ‘good’ trade does not automatically mean a winning trade, nor does a ‘bad’ trade automatically mean a losing trade. What matters is whether you followed your rules, but also whether those rules themselves were sound to begin with.

How do you check this? Ask yourself about the logic behind them. Do they make sense in terms of your trading history and/or market mechanics? (In case you’re not sure what I mean, look at Dr. Mansi’s rules on stop losses as an example.)

Another good test is to see whether you can explain (orally or in writing) your rules and decision-making processes to someone else, in a way that’s understandable to them.

Make learning from losers part of your process

This focus on process is also strongly linked to being able to invest in losses:

“In my experience, successful people shoot for the stars, put their hearts on the line in every battle, and ultimately discover that the lessons learned from the pursuit of excellence mean much more than the immediate trophies and glory.

“In the long run, painful losses may prove much more valuable than wins—those who are armed with a healthy attitude and are able to draw wisdom from every experience, ‘good’ or ‘bad,’ are the ones who make it down the road. They are also the ones who are happier along the way.

“Of course the real challenge is to stay in range of this long-term perspective when you are under fire and hurting in the middle of the war. This, maybe our biggest hurdle, is at the core of the art of learning.”

The whole journey towards ever-improving performance is just one big process. The entire journey can easily span a lifetime. Learn to enjoy the journey itself, not just the resulting profits — you will be much happier as a result and, dare I say it, wealthier too. True wealth constitutes of more than just money.

The parallel between the last paragraph of the above quote from Josh and trading with real money is also interesting. If you can make money with paper trading, great! But the real question is whether you can do it when you have real money on the line (i.e. are “under fire”) — and even more so, for the (aspiring) full-time traders among you, whether you can maintain your performance when you have no regular pay cheque (or alternative income stream) coming in as a backup. This isn’t something I’m aiming for myself, but what Josh says about keeping perspective sounds about right to me.

Journal

Since he was 12, Josh kept journals of his chess study, “making psychological observations along the way”.

Doing so produced at least one big eureka moment:

“I sat down with my laptop and chess notebooks and spent a few hours looking over my previous year of competitions. During chess tournaments, players notate their games as they go along. […]

“For a number of years, when notating my games, I had also written down how long I thought on each move. This had the purpose of helping me manage my time usage, but […] it also led to the discovery of a very interesting pattern.

“Looking back over my games, I saw that when I had been playing well, I had two- to ten-minute, crisp thinks. When I was off my game, I would sometimes fall into a deep calculation that lasted over twenty minutes and this ‘long think’ often led to an inaccuracy. What is more, if I had a number of long thinks in a row, the quality of my decisions tended to deteriorate.”

Notice, by the way, that while the discovery was related to Josh’s psychology, he essentially uncovered the pattern by looking at his numbers.

Regardless, it was a big moment for Josh, and it reminds me of the story David Ryan often tells of his early days, of how he took a weekend to review his trades across an entire year, during which he lost 69% of his account, and discovered the key mistake he’d been making. This permanently changed the course of his trading career.

The person who got me to forever change the way I approach journaling was Tom Dante.

The mechanics of creativity

This is something I’d never really thought about before, but the way Josh discussed the mechanics of creativity made a lot of sense to me. I’ve converted them into a step by step:

First, you must have knowledge.

This knowledge must be so deeply internalised that you can access it without thinking about it.

Then, you make a discovery — a leap that takes what you know one or two steps further.

There must be a connection between that discovery and what you know. Find it.

Figure out the technical components of your creation.

Use them to add your discovery to your existing knowledge, and trigger your creation at will.

Whether consciously or not, this is the sort of process you follow when getting knowledge (ideas) from other traders, then adapting them to suit your own style. You’d also be following it when studying recent big winners to find tradeable patterns in them.

Building resilience: the ‘soft zone’

We’re surrounded by distractions — it could be an alarm going off outside, a pet demanding our attention, someone knocking on the door… Take your pick. The point is, while you can work to minimise such distractions, particularly when working from home, you can never totally block them out. (It’s certainly something you can’t do when you’re performing in front of an audience, but that’s another situation altogether.)

Furthermore, the examples I named are just external distractions, but there are many internal ones too — for instance, being worried about a loved one, feeling the pressure of a recent losing streak, battling sickness (whether major or minor), or even just having a song stuck in your head. No doubt you can think of a few personal examples of your own to add to the list.

So when distraction inevitably occurs, how do you react? Do you try to block it out and/or strain your body to fight off the distraction? Then you are in a ‘hard zone’, which “demands a cooperative world for you to function. Like a dry twig, you are brittle, ready to snap under pressure”, to quote Josh.

Can you be in the ‘soft zone’ instead? Here are a few excerpts from the book that should help you get the idea:

“learn to flow with whatever comes. […]

“be quietly, intensely focused, apparently relaxed with a serene look on your face, but inside all the mental juices are churning. You flow with whatever comes, integrating every ripple of life into your creative moment. This Soft Zone is resilient, like a flexible blade of grass that can move with and survive hurricane-force winds. […]

“My idea was to become at peace with distraction, whatever it was. […] the solution to this type of situation does not lie in denying our emotions, but in learning to use them to our advantage.

“Instead of stifling myself, I needed to channel my mood into heightened focus […] My whole life I have worked on this issue. Mental resilience is arguably the most critical trait of a world-class performer, and it should be nurtured continuously. Left to my own devices, I am always looking for ways to become more and more psychologically impregnable.

“When uncomfortable, my instinct is not to avoid the discomfort but to become at peace with it. When injured, which happens frequently in the life of a martial artist, I try to avoid painkillers and to change the sensation of pain into a feeling that is not necessarily negative. My instinct is always to seek out challenges as opposed to avoiding them.”

I think this is an important concept, but one difficult to generalise. I certainly don’t feel like I can supply a solution that will work for every trader — this is something you’ll need to discover for yourself, possibly by reading Josh’s lengthy personal stories on the topic as well as the ones in other biographies.

It’s also something I could work on more myself. So far, my best trigger to get ‘into the zone’ is to play certain types of music, but the best song or playlist choice massively varies, depending on my mood that day, as well as on the type of work I’m doing.

The importance of recovery

Many traders work long hours, whether it’s because they are exceptionally hard-working, full-time traders, or because they are juggling the markets with another job.

Remember Josh’s journal example, about linking the quality of his thought processes in chess to the time he spent thinking? In his book, Josh continued as follows:

“The physiologists at [performance training centre] LGE had discovered that in virtually every discipline, one of the most telling features of a dominant performer is the routine use of recovery periods. Players who are able to relax in brief moments of inactivity are almost always the ones who end up coming through when the game is on the line. […]

“The notion that I didn’t have to hold myself in a state of feverish concentration every second of a chess game was a huge liberation. […] I learned to monitor the efficiency of my thinking. If it started to falter, I would release everything for a moment, recover, and then come back with a fresh slate. […]

“At LGE, they made a science of the gathering and release of intensity, and found that, regardless of the discipline, the better we are at recovering, the greater potential we have to endure and perform under stress.”

Personal examples

Josh gave several detailed examples of what he does to recover. I couldn’t copy them verbatim here without making this stack too long, nor shorten them without cutting vital details, so thought I’d share some of the things I personally do (for writing and trading) instead:

Two steps from my desk, in my office doorway, I have a pull-up bar. If I can feel my focus slipping, a couple of quick pull-ups and/or chin-ups literally take seconds to do, but are hugely refreshing to my mind. A few push-ups (and, I’m sure, various other exercises) work too, but the pull-up bar is my favourite.

A few steps further, I have a sink. Splashing my face with cold water is another quick but effective thing I can do to refresh my mind.

Go outside for a few minutes to get some steps in as well as some fresh air, and soak up some sunlight.

Head for the kitchen and make a cup of tea. (I am British, after all.)

This isn’t a complete list, but are my top go-tos that take minutes or even seconds to do, and enable me to keep going, with full focus, for a significant period afterwards. I would love to hear yours too — please do share them in the comments below!

Did the book help me?

When I read it as part of my other endeavour, it was useful (in a practical sense) in certain areas, such as developing a better understanding of the mechanics of creativity. In other words, how to help ‘make the magic happen’, rather than just waiting for inspiration to strike. I also felt inspired by reading about the lengths Josh went to in order to push himself to the next level. To where he wanted to be. I think this quote from the book phrases it very nicely:

“The fact of the matter is that there will be nothing learned from any challenge in which we don’t try our hardest. Growth comes at the point of resistance. We learn by pushing ourselves and finding what really lies at the outer reaches of our abilities.”

Quite aside from this, I thought the book an interesting and at times entertaining read. It was certainly very engaging. However…

The book didn’t enable or trigger a meaningful psychological breakthrough. Funnily enough, that came from a free series of YouTube videos, from a channel that offers top-quality content but presented in poor video quality. I assume that it’s because of the latter that it’s underappreciated.

And did this channel talk about psychology? Nope. It talked about technique in a very clear, no-nonsense manner. It talked about all the things the people really serious about that activity did on a regular basis. All the things you can and should do if you really want to become good at that activity.

In short, the videos opened my eyes to how — despite thinking I was serious about that activity, and spent 1–2 hours a day on it despite it only being a (serious) hobby — I wasn’t doing nearly enough to make reaching the next level possible. I was certainly not doing enough of the smart stuff to make that possible. Perhaps this mindset had always been ‘in’ me, and someone just had to flick a switch, but it was the realisation that I had to work harder, smarter and with more regular feedback — with some practical suggestions about concrete things to do — that marked my turning point.

And you know what? Being able to reach heights you didn’t think you could reach in one activity makes you believe that you can surprise yourself in other endeavours too, if you put your mind to them. Or at least, that’s what my experience was. I guess this aligns pretty closely to what Stockbee describes as “the number one secret to trading success”: self-efficacy.

More content like this

If you want to read more of my stacks on trading psychology, take a look here. The full archive for The Trading Resource Hub is here.

And if you want to get future articles like this straight to your inbox, feel free to subscribe!

Please do also let me know what you thought of this post. You’re more than welcome to disagree, just please keep the discussions respectful :) That way, we all get a chance to consider ‘the other side’, develop better-informed views of our own and ultimately grow as both people and traders.

You can leave a comment below, message me on Twitter or email me at kayklingson@yahoo.com. Also simply liking and/or sharing this post helps me grow my Substack!

A reader kindly recommended me some more practical trading psychology books, which I will read. I’m always trying to keep an open mind — if the information changes, my mind does too. In my last post, I did say how I could have simply not come across the good books on that topic, which is why I welcomed (and still welcome) recommendations.

Subscribe to The Trading Resource Hub

Gathering ideas from top performers and turning them into actionable insights to help traders improve. For educational purposes only; not financial advice.

Great review. Actually I prefer the longer piece as there is a coherency and no context switching needed (for me). Also, can you share the link to the YouTube videos you refer? Has piqued my curiosity!

Hi Kay, Great piece. It weaved several different ideas together well. One possible suggestion, depending on how often you plan to publish: I would try to make the articles into smaller bite sizes. This could have been a 2 or 3 parter, for example.